Carnegie Library - Wychwood

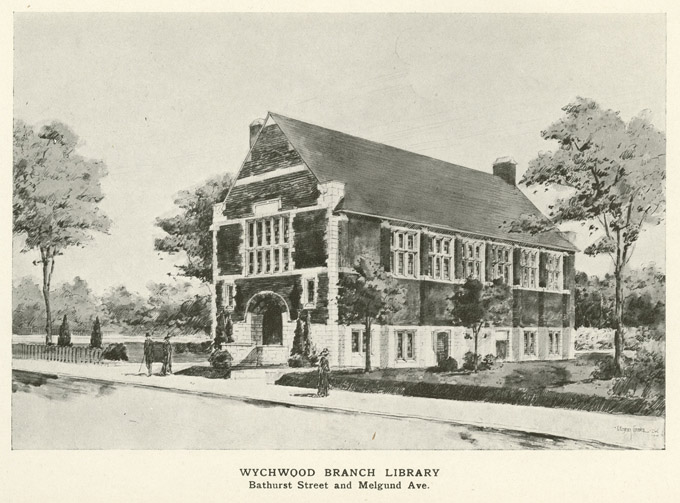

Architectural drawing of Wychwood Branch Library, 1915

Architectural drawing of Wychwood Branch Library, 1915From Toronto Public Library Annual Report 1915, between pp. 24 and 25.

Address: 1431 Bathurst Street, northeast corner of Melgund Road

Grant Date: 8 May 1908 (promised); 6 February 1915 (regranted)

Recipient: Toronto Public Library Board

Architect: Eden Smith & Sons

Opened: 15 April 1916

Wychwood Branch on the Digital Archive

Wychwood Branch opened on 15 April 1916, and was the prototype of three identical libraries that the Toronto Public Library constructed with a $50,000 grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

The design, an adaptation of the Tudor Gothic style, was "a decided revolt in style from the traditional library architecture," Chief Librarian George H. Locke proclaimed in January 1917, "and it is pleasant to record that the success of the Wychwood Branch is now being realized in the High Park Branch and in the Beaches Branch, both of which are of the same design."1

Locke enclosed a sketch of his proposed plan for the three new branches in his initial letter to James Bertram, secretary of the Carnegie Corporation, written on 22 June 1914. He noted that it had "been made to bring to the minds of the people of the outlying districts some recollection of their Scottish and English village type of architecture. These Suburbs are largely working classes from the countries mentioned."2

Locke reiterated his vision in a letter to Bertram, written on 13 March 1915:

May I point out to you that it is an almost entire departure from the traditional library building, but as I mentioned in a former letter to you, I am doing this as a result of my experience in having regard to the kinds of people who are living in this locality. These are people from the Old Country, accustomed to see in their country village's architecture of the 17th Century, and I am proposing to reproduce some of the Collegiate Grammar School architecture of the time of Edward 6th, and adapted to modern requirements.3

He went on to note, "I am fortunate in having for this purpose an architect whose work is distinguished on this Continent for its adaptation of English architecture to American requirements."4 Eden Smith and Sons, Architects had been hired by the library board, and Locke's March 1915 letter included the firm's "Description of a Branch Library Building", offering a rationale for the design:

An adaptation of English 17 Century collegiate style of Architecture was chosen for this building because the plan of its requirements and the material, brick and stone, found most convenient to use in erecting it are not at all appropriate for a monumental type of building of Greek or Roman origin.5

The architects also outlined the materials that they planned to use:

The basement is to be faced outside with grey stone to the height of the main floor. The external walls above this will be tapestry brick. The detail work, doors and windows, transoms, and mullions of gray stone like the basement. The roof is to be covered with gray green slate. The casements are to be glass with clear glass in lead bars.6

In 1926, Locke recalled he encountered some scepticism from local citizens about the architectural style:

When I was planning the Wychwood Branch I was reproached by a gentleman in this city who said, "It doesn't look like a library." I asked him what a Library looked like. He said he didn't know but he thought it ought to have columns in front. I found out that he had seen the so-called Library of the Early-Carnegie days with columns in front, rooms on either hand and a stack room in the back centre. Indeed it was an architect who told me a Branch Library, indeed any library, should be classical in style. I couldn't find out from him whether it was Greek or Neo-Greek he favoured.7

Major Alterations

1978 Renovation and addition by Phillip H. Carter, Architect.

1995 Retrofit by Robin Tharin Architects. Closed 18 November - March 25, 1996.

2014 Planning starts on branch renovation and expansion project: Shoalts and Zaback, project architects; Phillip Goldsmith, heritage architect. Construction began in 2018.

2022 Branch reopens in October, more than double its size from 6,380 to 17,200 square feet. Architects Shoalts and Zaback Ltd. have preserved the historical building, adding on a two-storey addition to improve accessibility and meet the needs of a growing community.

Heritage Status

1976 Listed on Inventory of Heritage Properties, adopted by Toronto City Council, August 18.

Notes

1Toronto Public Library, Annual Report, 1916, 11.

22Carnegie Corporation of New York, Carnegie Library Correspondence, Toronto, reel no. 32 (CLC), Locke to Bertram, 22 June 1914. (Hard copy in Toronto Public Library Archives)

3Ibid., Locke to Bertram, 13 March 1915.

4Ibid.

5Ibid., Eden Smith & Sons, "Description of a Branch Library Building".

6Ibid.

Early Library Service in the Wychwood - Bracondale Area

Before the Carnegie-funded Wychwood Branch Library opened on 15 April 1916 on Bathurst Street at the northeast corner of Melgund Road, local library service was provided in four buildings, initially by the Bracondale Public Library, 1898 to 1911, and thereafter by the Toronto Public Library.

1. Bracondale Post Office, southwest corner of Davenport Road and Christie Street, 1898-1901

Bracondale Post Office, southwest corner of Christie Street and Davenport Road, about 1890

Bracondale Post Office, southwest corner of Christie Street and Davenport Road, about 1890City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 2, Series 8, File 40, Item 1

Bracondale Public Library was organized at a "very well attended meeting at Turner's Hall held on Thursday last," the Toronto Globe reported on Saturday, 21 May 1898. "Great interest was manifested by all the parties present. A large list of members was handed in. ... Mr. Turner promised all the assistance in his power."1

Turner's Hall was a community meeting space on the upper floor of Bracondale Post Office, a two-storey frame building that Frank Edwin Prince Turner (1838-1909) constructed a few years before he was appointed as the first postmaster on 1 May 1883. He was the prime promoter of Bracondale village, which sprang up around the Turner family home, Bracondale Hill, built in the late 1840s by Frank's father, Robert John Turner (1795-1873), who registered the first subdivision plan (number 119) of his estate on 9 May 1855.

The first directors of the new public library were elected at the meeting on 19 May 1898, and they included some of Bracondale's most prominent citizens: "Miss Turner, Dr. T. Page, Dr. W. McNab, F. C Miller, M. Brimacombe, C. Greensides, F. Huntley, W. Caldicott, E. Boggis," the Globe listed.2

Considering that Frank Turner had pledged his assistance to the new library, and that both his deputy postmaster, Edwin Charles Boggis (1851-1937), and his older sister, Mary Emma Turner (1837-1906), were on the inaugural board, the library's first location probably was Bracondale Post Office. Boggis was the deputy postmaster from 1884 to 1901, and, for most of that time, he and his family lived in the post office building where he also operated a grocery store. He served on the Bracondale Public Library Board from 1898 until it was disbanded in 1911. The post office building was demolished in 1912 when Christie Street and Davenport Road were widened.

By the end of April 1899, when the Bracondale Public Library Board made its first report to provincial officials, it had received $122.86, spent $117. 28 and its assets were valued at $99.38; the library had 103 members who had borrowed the 147 books in the collection 486 times.

The library probably remained in the post office until 1901, when Boggis gave up being the deputy postmaster to work in the neighbouring tannery/leather factory that his cousin, John E. Edwards (1836-1900), had started in the early 1880s.

2. J. E. Edwards & Sons Tannery/Leather Factory, Christie Street, southeast corner of Benson Avenue. 1901-February 1904

J. E. Edwards & Sons Tannery/Leather Factory, Christie Street, southeast corner of Benson Avenue, 31 July 1913.

J. E. Edwards & Sons Tannery/Leather Factory, Christie Street, southeast corner of Benson Avenue, 31 July 1913.City of Toronto Archives Fonds 1231, Item 442

In March 1901, the Toronto Star reported, "Bracondale Public Library was offered a free site upon which to build its new reading room and library, and a subscription will be taken up to assist in erecting the building."4 That May, one report from Bracondale stated, "Plans and specifications for the new Public Library are being prepared,"4 while another noted, "Gregg and Gregg, architects, of Toronto are preparing plans for new library building here."5

By March 1902, the library board was meeting "in the Library building, Christie street north."6 A report in May stated that the library "is in a flourishing condition and is well patronized by the residents. There are about 1,500 books on the shelves."7

Apparently the "Library building" was within the J. E. Edwards & Sons Leather Goods factory, located since 1900 on Christie Street at the southeast corner of Albert Street (Benson Avenue). (An earlier factory on Christie Street near the northwest corner of Victoria Street (Tyrrell Avenue) was destroyed by fire in 1899.) The library and reading room occupied one or two rooms next to the enameling shop.

Fire struck again on 13 February 1904 when the enameling shop was gutted and, except for the books that were out on loan, almost all of the 1,500 volumes in the adjacent library were destroyed, along with its furniture and records; the library's loss was estimated at $3,000. The librarian, William (Billy) Garrett (1869-1938), was a "japanner" at the factory, and he continued to serve on the Bracondale Public Library Board until the end of 1907.

In 1913, the factory site was expropriated by the City of Toronto, which demolished the building and constructed car barns there for the Toronto Civic Railways' St. Clair streetcar line (The Edwards family relocated their operations to Cobourg, Ontario.) Now known as Artscape Wychwood Barns, the old car barns are used for a variety of community activities.

3. Wychwood (Fire) Hall, Alcina Avenue, north side, west of Bathurst Street, March 1904-June 1905

Looking east on Alcina Avenue, about 1907. The tower of Wychwood Fire Hall is visible on the far left.

Looking east on Alcina Avenue, about 1907. The tower of Wychwood Fire Hall is visible on the far left.City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 2469

On 17 February 1904, four days after the fire, the Bracondale Public Library Board held a special meeting at the office of J. E. Edwards & Sons on Christie Street, and accepted an offer to relocate the library to Wychwood Hall, instructing "necessary expenditure not to exceed $35."8 Later that month, the Toronto Star reported that "it was expected that the board will be able to open up about the first week of March. Members who have paid their subscriptions will kindly produce their receipts as all records were lost in the fire."9 The library was housed in the lower part of the hall, and remained there for about a year. By the end of December 1904, its collections, which had been reduced to about 300 books by the fire, had increased to 880 volumes.

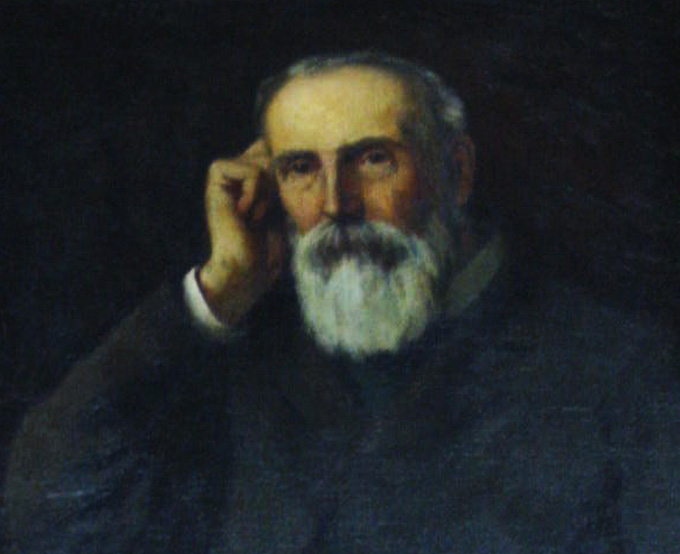

Marmaduke Matthews, portrait by George A. Reid, 1898.

Marmaduke Matthews, portrait by George A. Reid, 1898.Toronto Public Library. Wychwood Branch

Wychwood Hall was built around 1892, the year that it was announced: "A fire hall and large assembly room is to be erected at Wychwood Park, North Toronto"10 Slightly east of Bracondale, Wychwood Park was named after Wychwood Forest in Oxfordshire, England by Marmaduke Matthews (1837-1913), a landscape painter. He built the first house in the park in 1874 hoping to establish an artists' colony.

Wychwood Hall was used by the volunteer Wychwood Park Fire Protective Association as well as various religious groups, fraternal societies and other organizations. It was replaced by Toronto Fire Hall No. 25 (now Station 343, Toronto Fire Services), which opened in 1911 on the east side of Hendrick Avenue, just south of St. Clair Avenue West. The new fire hall (which continued to be called Wychwood Hall for many years) was designed in 1910-11 by Robert McCallum, the City Architect, who also planned three Carnegie-funded branches for Toronto Public Library around that time: Yorkville, Queen & Lisgar and Riverdale.

4. Hillcrest Public School, Bathurst Street, east side, between Hillcrest Avenue (Hilton Avenue) and Nina Avenue, July 1905-March? 1916

At a special meeting held at Wychwood Hall on 23 February 1905, the Bracondale Public Library Board accepted an offer from the trustees of School Section No. 25, York Township for "free quarters in new school including lighting & heat."11 Hillcrest School opened with six rooms in May 1905, and the library board met there for the first time on 5 July 1905. Matthew B. Holmes, the first principal of Hillcrest School was then the secretary of the Bracondale Library Board. (He continued as the school's principal almost continuously until his retirement in the 1930s.) Enrolment in the school grew quickly, and in 1906, the library's space was taken over for a classroom. "This puts the library, 1,400 volumes, on six shelves at the back of the room," the Toronto Star reported that September, "and if the librarian was not a tall man he could not reach the top shelf. These shelves are hung with muslin curtains to keep the children at school from handling the books." Noting that use of the library was increasing in the growing community, the Star suggested, "if the Library Board would show some signs of life there is no reason why a handsome building should not be erected for this purpose and rechristened the Wychwood Public Library."12

Hillcrest School soon was enlarged, and in April 1907 a deputation from the library board was sent to meet with the school trustees "in regard to fitting up of new Library room."13 Evidently successful, the board soon increased access to the library. The librarian was empowered in November 1907 to let customers select books from the shelves on their own, and in January 1908 pupils at the school were allowed to use the library "at discretion of Principal on payment of 5 cts."14

Hillcrest School was taken over by the Toronto Board of Education after the Wychwood and Bracondale districts were annexed to the City of Toronto on 1 February 1909. The following month, Matthew Holmes wrote to George Locke, chief librarian at Toronto, asking "Cannot the [Bracondale] Library be made a branch of the Toronto Public Library. We are 3 miles from the nearest branch. 5000 books were borrowed from the Library last year. If you or any member of the Board cared to have a look at it I would be pleased to show you on any school day."15

Toronto Public Library did not follow up with this request until 1911, which was a year of important developments for local library service. In March, a delegation told the Toronto Public Library Board that Bracondale Library was starved for funds since government grants had ceased after annexation, and that they planned to discuss their "vested rights" to the library room at the school with the Toronto Board of Education. Locke subsequently visited the Bracondale Public Library and in early June 1911 recommended that Toronto Public Library Board take over its operation. "Following some months of negotiation with the Board of Education, the Bracondale Public Library," Locke later reported, "was recognized as having proprietary rights in the room dedicated for the purpose of a public library prior to annexation."16 In October, the assets of the Bracondale Public Library, including $56.10 cash on hand and 1,777 books, were transferred to the city library board, and Toronto Public Library staff began "repairing, rebinding, accessioning, numbering, classifying and cataloguing them."17

Wychwood Branch opened in the library room on the second floor of Hillcrest School on 2 February 1912. Described as a "successful experiment," it was the first branch that Toronto Public Library operated in a school.18 About 1,100 of the 1,600 volumes in the new branch came from the old Bracondale Public Library. Wychwood and Deer Park were the first circulating libraries in Toronto Public Library to have their own card catalogues.

Wychwood Branch initially was open Mondays afternoons from 2:30 to 5:30 and Fridays from 4 pm to 8:30 pm. In 1912, along with Riverdale Branch, it was the first location for "story-telling sessions", a new service that Toronto Public Library inaugurated in September. By the end of 1913, Wychwood Branch was open both afternoons and evenings on Mondays and Fridays, and it had 3,285 books that circulated 10,338 times that year, the majority being adult fiction and juvenile books.

The library was not adequate to meet local demands, however. In February 1915, a "Disgusted" local resident, wrote about "The Wychwood Library" in a letter to the Toronto Star: "It is upstairs in the Hillcrest Public School, in a room somewhere about 10' x 12'. The books there are splendid, but there cannot be new ones, as the shelves have been filled for months, and there is no place to put more. Then, it is an awkward place to get to, and it must cause inconvenience to the school.19

Miss Webb, the librarian at the branch, was even more direct about the "poky little room in Hillcrest School" when she talked to a reporter from the Evening Telegram a few weeks later:

Here we have a very small room ... and the books are jammed into every conceivable corner in the effort the make room for them. It is impossible for us to circulate more than the seven hundred of the two thousand books were have in stock here, and it is absolutely impossible to get in any new books, as we have no room for them. They are jammed into places where the people are unable to reach them.20

Wychwood Branch remained in Hillcrest School until shortly before the new Carnegie-funded branch officially opened at the northeast corner of Bathurst Street and Melgund Road on Saturday evening, 15 April 1916. One of the speakers at the event was William Houston, chairman of the Toronto Board of Education, who stated, the Globe reported two days later, "that while he had always predicted that the district would develop into one of the finest sections of the city, he believed that "Hillcrest" would be have been a more appropriate name than "Wychwood" for the new structure."21

Notes

1 "Bracondale," Toronto Globe, 21 May 1898, 19.

2 Ibid.

3 "Bracondale," Toronto Star, 22 March 1901, 7.

4 "Bracondale," Toronto Star, 13 May 1901, 4.

5 "Contracts open," Canadian Contract Record, 7 (29 May 1901), 2

6 "Bracondale," Toronto Star, 4 March 1902, 11.

7 "Bracondale," Toronto Star, 3 May 1902, 11.

8 Bracondale Public Library Board minutes, Special meeting, 17 February 1904, 1. (Toronto Public Library. Wychwood Branch Local History Collection.)

9 "The Bracondale Library," Toronto Star, 23 February 1904, 7.

10 "Contracts open," Canadian Contract Record, 3 (27 August 1892), 2.

11 Bracondale Public Library Board, Minutes, 23 February 1905.

12 "Wychwood," Toronto Star, 14 September 1906, 6.

13 Bracondale Public Library Board, Minutes, 19 April 1907, 14.

14 Ibid., 13 January 1908, 16.

15 Toronto Public Library Archives, L2, Box 12.

16 Toronto Pubic Library, Annual Report 1911, 12.

17 Toronto Public Library Board, Libraries and Finance Committee, Minutes, 7 November 1911, 26.

18 "Will libraries open on Sunday?" Toronto Star, 15 December 1911, 9.

19 "The Wychwood Library, Toronto Star, 4 February 1915, 5.

20 "Wychwood - Library is inadequate," Evening Telegram, 16 February 1915.

21 "Wychwood Library is formally opened," Toronto Globe, 17 April 1916, 9.

Carnegie Library - Wychwood, 1914-1915

Planning and Opening

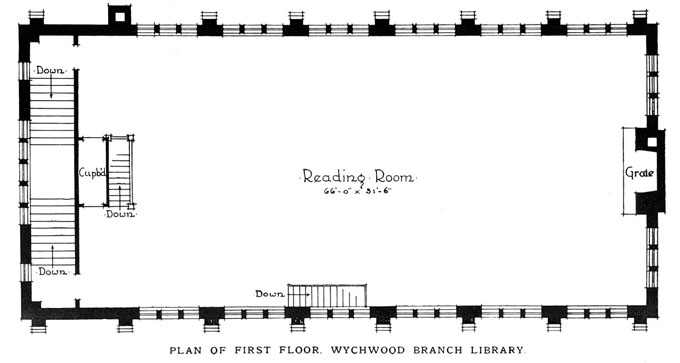

Plan of First Floor, Wychwood Branch Library, 1915

Plan of First Floor, Wychwood Branch Library, 1915Eden Smith and Sons

Toronto Public Library Annual Report, 1915, p. 43

Wychwood was the prototype for the three libraries that Toronto Public Library opened in 1916 with a $50,000 grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The design was a collaborative effort by Chief Librarian George H. Locke and Eden Smith & Sons, a prominent Toronto architectural firm, with input from James Bertram, secretary of the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

On 9 June 1914, Locke reported to the Board's Libraries and Finance Committee that he had recently learned that "a supplementary grant of $50,000 had been set aside by the Carnegie Corporation for the use of the Toronto Public Library Board." He stated "that he had in conjunction with an architect designed a small Branch Library building - a sketch which he submitted - which could be put up for $15,000," and it could be "applied to the erection of branch buildings to supply the Deer Park [i.e. High Park], Wychwood and Beaches districts."1

In his initial letter to Bertram on 22 June 1914, Locke enclosed the sketch of his "tentative plan for a group of three Branch Libraries in three far-outlying portions of our city were the need is particularly pressing".2

Four month later, Bertram responded to the plan, using the simplified spelling that Andrew Carnegie advocated. Writing to Locke on 29 September 1914, he commented that, although Toronto had talked about "three bildings in outlying parts of the city", it had sent "only one plan as a colord drawing shoing one large room on the ground floor and a hall, etc. in the basement. This plan appears to be very satisfactory."3

Locke responded to Bertram the following day, noting, "the coloured drawing sent you was a tentative general plan made by me and submitted as the kind of building suitable for the new portions of our fast growing city. As it was out of the ordinary I wanted to submit it first to you before I go on with the working drawings."4

In fact, the plan reflected recommendations that Bertram had made in his 1911 memorandum, "Notes on the Erection of Library Bildings," such as providing:

- A rectangular building;

- One storey and basement with an outside staircase;

- One large room subdivided by bookcases;

- A basement four feet below grade;

- Ceiling heights of nine feet for the basement and 12 to 15 feet for the main floor;

- Rear and side windows seven feet from the floor to allow continuous wall shelving;

- A lecture room as a subordinate feature in the basement.5

On 9 March 1915, Locke submitted a set of plans to the Library Board "for the proposed Wychwood Branch building, drawing up by Messrs. Eden Smith & Sons under his direction".6 The plans were approved, and Locke sent them to Bertram several days later, also enclosing a "Description of a Branch Library Building" written by the architects.

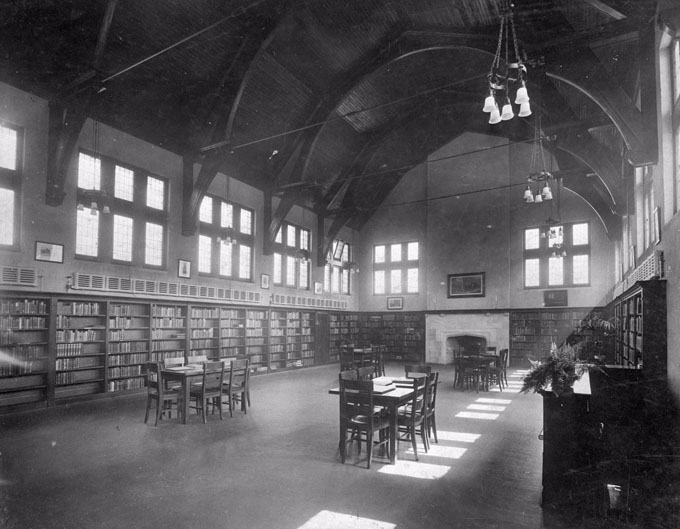

The Reading room and Library, 70 feet long by 30 feet wide, raised about 7 feet above the ground level, is really a large hall with an open timbered roof, the walls above 19 feet high to the springing of the roof. The ceiling 29 feet at its apex. The stairs from the Bathurst Street entrance lead into this hall from under a gallery screen. At the other end of the room is a large stone fireplace. Bookshelves line the walls on each side to a height of about eight (8) feet. Above the shelving all round the room transomed and mullioned windows provide plenty of light. ... 7

Curiously, Bertram made no comment about the height of the ceiling, which was twice as high as what he recommended in his "Notes". In 1913, he had not allowed a ceiling of 16 feet nine inches in the main floor of Weston Public Library but, as Locke observed, "Mr. Bertram is not noted for being consistent."8

The completed room was described in great detail in January 1921 by a reporter from the Toronto Mail and Empire:

Inside the walls of soft French grey stucco form an effective backdrop for numbers of quaint Dickens engravings which are hung at intervals around the long room. Below these, dark oak bookcases line the walls filled with books of every description and the vari-colored bindings lend the needed dash of color to brighten up the grey and dark oak, color-scheme. At one end of the room there is a large stone fire-place where a cheery fire burns on cold days. At the other end is the receiving desk where the books are returned and taken out ... The high ceiling has the heavy oaken rafters and the middle of the room are tables and chairs where current issues of leading magazines and periodicals may be read.9

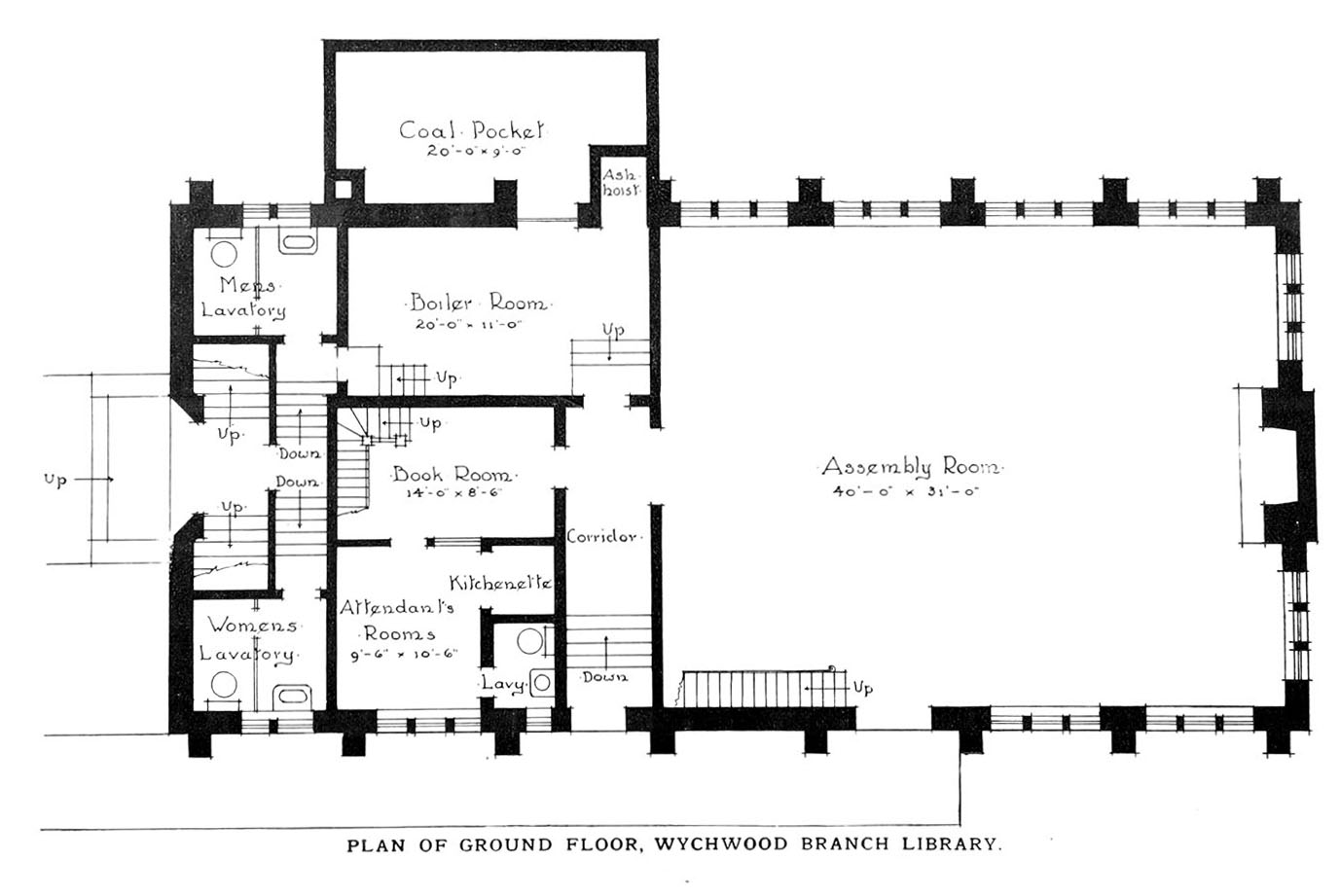

Plan of Ground Floor, Wychwood Branch Library, 1915

Plan of Ground Floor, Wychwood Branch Library, 1915Eden Smith and Sons

Toronto Public Library Annual Report, 1915, p. 42

Eden Smith & Sons also outlined the ground floor plan in their 1915 "Description of a Branch Library Building":

Below this hall is the basement floor, 10 feet in height, 4 feet of which height is below ground containing, as well as lavatories, boiler and other necessary rooms, an Assembly room 30 x 39 with independent entrances to Melgund Street [i.e. Road].10

The Toronto Globe repeated the description, almost word for word, on 15 July 1915, but the assembly room was now called "a children's room, 30 x 39"11. At the official opening ceremonies of Wychwood Branch held on Saturday evening, 15 April 1916, Locke "pointed out that the basement had been constructed for the exclusive use of the children, while the main floor, with open shelves extending around the entire room, will be used by adults."12

The Mail and Empire 1921 report also described the finished ground floor:

Downstairs there is a cosy little sitting-room with wicker furniture and a complete kitchenette for the library girls where they may make tea every afternoon. Downstairs also is the Children's Library, which is just as complete in every detail as the grown-up's, and judging from the number of child members it must be both an incentive to study and a source of delight.13

Like Bertram, Locke favoured simple one-room libraries that would allow the main function, "the intermingling of books and people, to occur unimpeded." He explained his ideas in the May-June 1926 issue of The Journal Royal Architectural Institute of Canada:

Take away all unnecessary decorations, over-mantels, over-counters, partitions, mock marble pillars and large hall-ways, and plan a well-proportioned room with books on the wall, small and few tables, a simple charging desk (not a great counter), simple lighting as near the books and the people as possible and a combination of colours in the walls that makes for harmony. Take away all the 'Silence' signs and let the people come and talk about books in an atmosphere of social happiness.14

Notes

1 Toronto Public Library Board, Libraries and Finance Committee, Minutes, 9 June 1914, 123-4.

2 Carnegie Library Correspondence (CLC), Locke to Bertram, 22 June 1914.

3 CLC, Bertram to Locke, 29 September 1914.

4 CLC, Bertram to Locke, 30 September 1914.

6 Toronto Public Library Board, Libraries and Finance Committee, Minutes, 9 June 1914, 123-4.

7 Eden Smith & Sons, "Description of a Branch Library Building," enclosure in CLC, Locke to Bertram, 13 March 1915.

8 Locke to W. T. J. Lee, 20 May 1915. Toronto Public Library Archives, L2, Box 14a.

9Rita McBride, "The Wychwood library," Toronto Mail and Empire, 22 January 1921.

10 Eden Smith & Sons, "Description of a Branch Library Building," enclosure in CLC, Locke to Bertram, 13 March 1915.

11 "Wychwood Branch Library will be well laid out," Toronto Globe, 15 July 1915, 7

12 "Wychwood Library is formally opened," Toronto Globe, 17 April 1916, 9.

13 McBride, "The Wychwood library."

Carnegie Library - Wychwood, 1898-1916

Construction and Costs

Wychwood Branch cost $20,075.33 to build. That amount was about 40 percent of the total $50,000 grant that the Carnegie Corporation of New York awarded to Toronto Public Library to construct three almost identical libraries, which opened in 1916.

Wychwood was the prototype library. On 22 March 1915, James Bertram, secretary of the Carnegie Corporation, wrote to Toronto Public Library's Chief Librarian George H. Locke that it would approve the plans for the first branch (Wychwood) at $20,000 on the understanding that it had title to the site and the other two branches (High Park and Beaches) could be completely built and ready to occupy for a total of $30,000.

About two weeks before, the Toronto Public Library Board had approved the plan for the proposed Wychwood Branch "prepared by Messrs. Eden Smith & Sons in consultation with the Chief Librarian" and had accepted ten tenders totaling $16,772.50 for its construction, "subject to the approval of the plans by the Carnegie Trust and the usual clause being embodied in each contract calling for the payment of union wages."1

Locke refused to start construction on the first branch, however, until the Toronto Public Library, rather than City Council, held the deed for the property. It was not until 27 July 1915 that the Toronto World reported, "The chief librarian fulfilled his promise that within 24 hours of the delivering to the public library board of the deed of the property on the corner of Bathurst and Melgund streets work would commence."2

On the same day, the Toronto World and several other city newspapers announced the names of the "successful tenders for the erection of the building under Eden Smith & Sons architects."3 Seven of the contracts were awarded to the same firms that the Library Board had approved in March 1915 and three were different. The following day, Locke reported to Bertram that "the contracts are all in and have been signed."4

Progress on building the library was rapid. By early September 1915, the foundation was finished and at the end of October, when the cornerstones for High Park and Beaches were laid, the Globe reported that Wychwood Branch was "now nearing completion."5 E. S. Caswell, the library's secretary-treasurer, relayed similar information to the Carnegie Corporation on 1 November 1915: "Wychwood Branch is well advanced, the roof now well on to completion."6 A week later, Locke boasted to the Board's Libraries and Finance Committee: "The progress of the work on our Wychwood Branch exceeds that on any building we have ever erected, and we are assured by other builders that it is a record in this city. All brick and stone work is finished and the roof is being put on."7 Locke continued to brag to the committee about the speed of construction on 11 April 1916, only a few days before the branch opened: "It has been built within eight months - a record in library construction in Toronto."8

Business card of H. N. Dancy & Son

Business card of H. N. Dancy & SonConstruction, April 1915, 2.

A little more than half of the funds allocated for Wychwood had been spent by the end of 1915 ($10,287.62) and the remainder were expended in 1916 ($9,787.71). The highest expenditure was for masonry ($8,531 to H. N. Dancy & Son) followed by carpentry ($3,386 to Chas. Cooper & Son), heating ($1,456.64 to A. W. Wilson) and plumbing ($854.96 to Sheppard & Abbott). The roof trusses to support the high ceiling were installed by McGregor & McIntrye for $500. The electric lighting fixtures were purchased for $419 from Jas. Morrison Brass Mfg. Co., and they "stood out prominently, a feature very important in a modern library,"9 Locke commented at the branch opening. Eden Smith and Sons were paid $884.92 for their work to design and supervise construction of the branch, or about 4 percent of its total cost.

Notes

1 Toronto Public Library Board, Minutes, 12 March 1915, 141.

2 "Wychwood Public Library," Toronto World, 27 July 1915, 2.

3 Ibid.

4 CLC (Carnegie Library Correspondence), Locke to Bertram, 28 July 1915

5 "Corner-stones are laid for two libraries," Toronto Globe, 30 October 1915, 9.

6 CLC, Caswell to Franks, 1 November 1915

7 Toronto Public Library Board, Libraries and Finance Committee, Minutes, 9 November 1915, 165.

8 Ibid., 11 April 1916, 179.

9 "Wychwood Library is formally opened," Toronto Globe, 17 April 1916.

Carnegie Library - Wychwood, 1914-2014

Site Acquisition and Changes

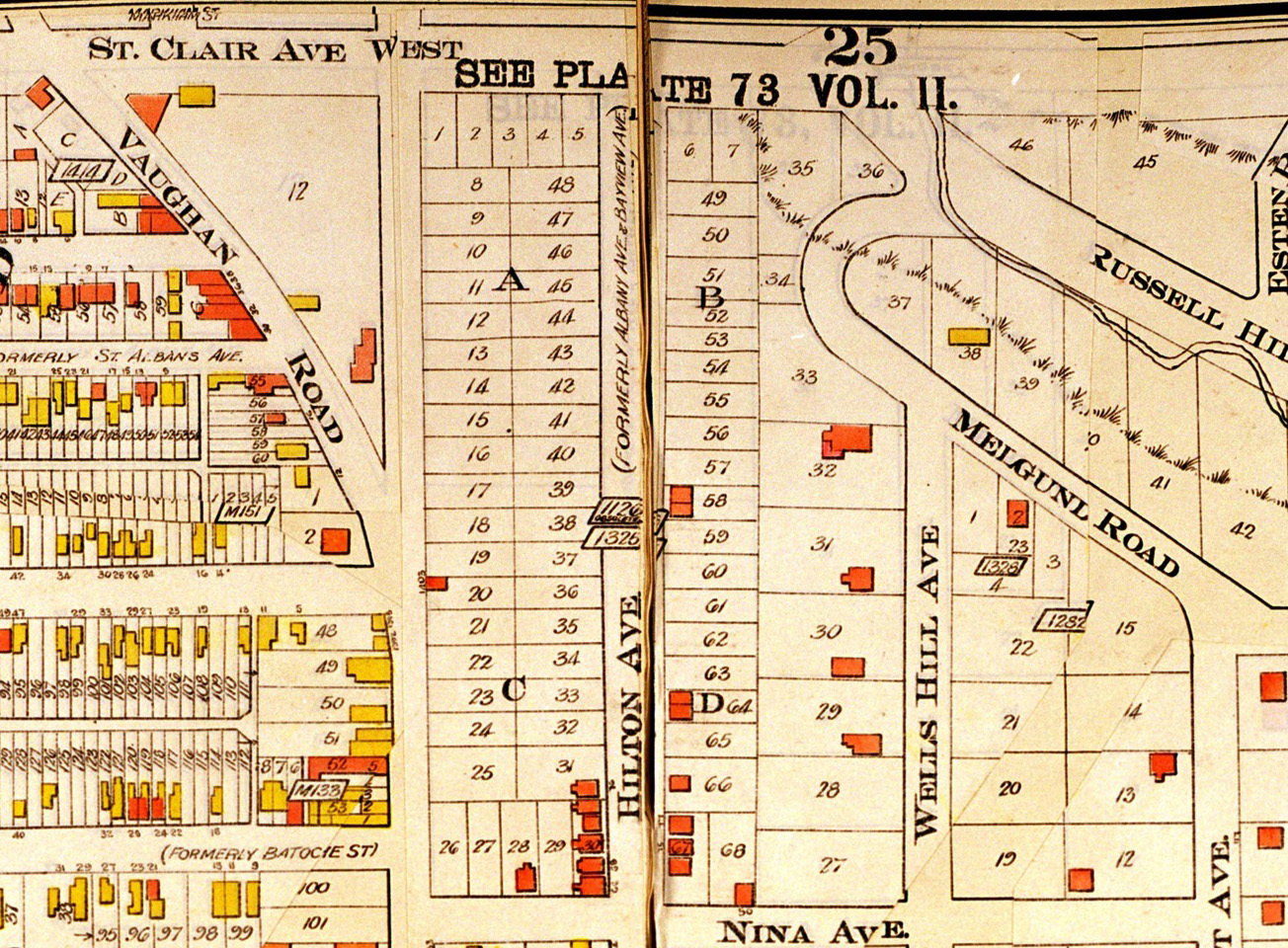

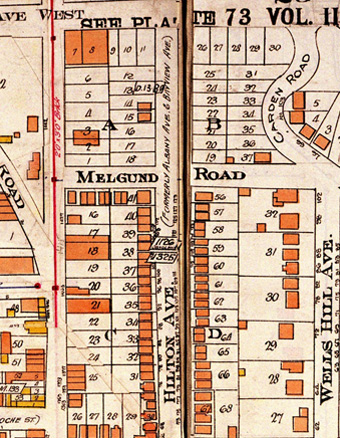

In April 1914, local residents began advocating for a site for a new library to replace "the small, inconvenient & altogether inadequate premises" at Hillcrest School, so described by J. W. Tibbs of the Bathurst Street Ratepayers' Association to the Toronto Public Library Board on 17 April 1914. The Association favoured a 600- by 200-foot block of land at the corner of Bathurst Street and St. Clair Avenue for the new library branch.1

Later that month, a deputation of the Hillcrest Ratepayers' Association asked the Board of Control "for the retention of a block of land on the south side of St. Clair Avenue, between Bathurst street and Melgund road, for public library and park purposes," the Toronto Star reported. "This property is already in the possession of the city, having been purchased by the Works Department for purposes of the St. Clair avenue "fill""2 Part of the city-owned property was also used for an extension of Melgund Road westerly from Wells Hill Avenue to Bathurst Street, authorized in two bylaws that Toronto City Council passed in 1913.3

Neighbourhood in the vicinity of proposed site of Wychwood Library, 1913

Neighbourhood in the vicinity of proposed site of Wychwood Library, 1913Detail of Plate 37, Goad's Atlas of the City of Toronto, 1913

Chief Librarian George H. Locke quickly apprised the Board's Libraries and Finance Committee of the second newspaper report, noting: "The deputation met with fair promises and are hopeful that this recommendation will be acted up by the Council."4

Toronto City Council was slow to provide a site for the new library, however, causing considerable dissatisfaction in the local community. "Quite an agitation has been stirred up among the residents here," the Evening Telegram reported from Wychwood in mid February 1915, "because of the apparent disinclination of the city to deed over the civic property on the corner of Melgund avenue [i.e. road] and Bathurst street, to the Public Library Board".5

Later in February 1915, sites for branch libraries at Wychwood and High Park were recommended to Toronto City Council. The Hillcrest Ratepayers' Association soon presented "a largely signed petition" to the Board of Control, who in early March agreed to transfer the property to the Library Board.6

On 1 May 1915, Locke was notified by James G. Forman, the city's commissioner of assessment, that the Wychwood site had been retained:

I have been requested by the Board of Control to retain, as a Library Site, Lots 1, 2, and Part of Lot 3, Plan D-1380, situated at the north-east corner of Bathurst Street and Melgund Road. The said land has a frontage of 100 feet on the east side of Bathurst Street, by a depth of 125 feet along the north side of Melgund Road.7

In the next part of his letter, Forman showed an ignorance or perhaps a misunderstanding of a key Carnegie grant condition that the local municipality must provide sites for Carnegie-funded libraries:

Kindly inform me at your earliest convenience if your Board is desirous of purchasing this property. The price quoted in my report to the Board of Control was $13,125.00, and in the event of your Board's acceptance, this amount will be charged to your appropriation for the current year. I may add, that an application has been made to use all the land for park and playground purposes, and if your Board is going to build this year, it will be necessary to reserve your proposed property from being so used.8

Further complications arose because the Library Board preferred that sites for the proposed branches be deeded to it and not held by Toronto City Council. James Bertram of the Carnegie Corporation favoured city ownership, though, and explained his views in a letter to Locke on 17 May 1915 (using the simplified spelling Andrew Carnegie advocated):

Our usual rule is to hav title to the library site vested in the community, i.e., the city, for account of the library. If the deed specifies that the site is for library purposes ther is no danger of anything going wrong. We ar averse to Mayors and City Councils being kept out of library matters as if they were not to be trusted.9

After weeks of wrangling, the city finally retracted their opposition to the Library Board holding the deeds, as the Toronto World reported on 30 June 1915:

The board of control yesterday decided to hand over to the library board the deeds for the sites at the Beaches, Roncesvalles avenue and Wychwood. This now puts the board in the position to draw on the Carnegie trust fund, which it was impossible to do until they had the deeds for the sites. The city solicitor reported against the handing over of the deeds, but on the motion of Mayor Church the controllers came to the above decision with the exception of Controller Spence.10

The issue finally was resolved at the end of July 1915 when, the Toronto World reported: "The chief librarian fulfilled his promise that within 24 hours of the delivering to the public library board of the deed of the property on the corner of Bathurst and Melgund streets work would commence."11

Landscaping the Site, 1916-1925

Landscape plan for Wychwood Branch by W. E. Harries and A. V. Hall, landscape architects, 1917

Landscape plan for Wychwood Branch by W. E. Harries and A. V. Hall, landscape architects, 1917Construction, v. 10 (November 1917), 392.

Landscaping the three new Carnegie libraries was underway by early November 1916, when Locke informed the Library Board's Libraries and Finance Committee: "Arrangements have been made for the planting of shrubs, perennials, and trees at Wychwood, High Park and Beaches. These must be planted in the fall to produce desired results."12

The grounds were planned by landscape architects William Edward Harries and Alfred V. Hall. "It was felt that if an individual treatment were possible for each site, the effects would be especially pleasing as the buildings themselves were so similar," Hall wrote in 1917.13

The partners had been working at their profession in Toronto since May 1912 and had established their own firm on 1 January 1914. Their early work included laying out gardens for R. S. McLaughlin's Parkwoods in Oshawa, W. F. Eaton's Ballymena in Oakville and Home Smith's original tea room at the Old Mill, as well as the grounds for Toronto General Hospital's new location on College Street.

Located at the corner of a vacant block and despite being relatively small in size, the Wychwood Library site was planted with representatives from 41 botanical families, 76 sub-families and 276 varieties of these. Care was taken to include native varieties and to group botanic families together. Dwarf evergreens were placed at the entrance, viburnums and honeysuckle in the shade along the north fence, a hedge on the east wall and 67 varieties of the rose family, from astilbe to spirea, along the south side. To promote public education and to give local residents an opportunity to discover shrubs that they could use in their own gardens, each of the plants had labels with their scientific and common names.

"A gardener of more than average ability is required to care for it from year to year," Hall warned, but Toronto Public Library's capable custodial staff was up to the task. A reporter from the Mail and Empire observed in 1921, "In the summer the grass is beautifully kept with beds of bright flowers standing out in bold relief against the green velvet of the lawn."14 In 1925, the St. Clair Horticultural Society presented Wychwood Branch with a silver cup "for the best-kept public grounds in the district."15

Wychwood Library site, 1924

Wychwood Library site, 1924Detail of Plate 37, Goad's Atlas of the City of Toronto, 1924

Silver cup presented to Wychwood Branch in 1925

Silver cup presented to Wychwood Branch in 1925Toronto Public Library. Wychwood Branch

Wells Hill Lawn Bowling Club's Use of the Site, 1944-Present

Wells Hill Lawn Bowling Clubhouse, about 2016

Wells Hill Lawn Bowling Clubhouse, about 2016Used with permission of Wells Hill Lawn Bowling Club.

In 1929-30, the Wells Hill Lawn Bowling Club became the library's neighbour on Melgund Road to the east. Sometime after its establishment in 1925, members of the Wells Hill Community Association discussed establishing a lawn bowling club, and formed a committee to apply to Parks Commissioner Chambers "to convert the vacant land at the [northwest] corner of Melgund Road and Hilton Avenue into a bowling green."16 In 1929, it was announced at a meeting held in the basement of Wychwood Library that the application had been granted. The name of the association was changed to Wells Hill Lawn Bowling Club in 1930 with the first election of officers.

As membership in the lawn bowling club increased over the years, a clubhouse was wanted. In May 1944, the Parks Commissioner approached the Toronto Public Library Board "for permission to erect a fieldhouse on a strip of adjacent library property at the Wychwood Branch Library," but the Board "regretfully" refused the request in November 1944.17

Architectural rendering of the rear exterior of Wychwood Branch renovation, showing the lawn bowling club's new facilities, 2014.

Architectural rendering of the rear exterior of Wychwood Branch renovation, showing the lawn bowling club's new facilities, 2014.Shoalts and Zaback Architects/Toronto Public Library

Unwilling to accept the decision, a deputation consisting of Alderman John Innes and two members of the lawn bowling club appeared before the Library Board on 13 March 1945 urging it "make available a strip of Library property 4 yds. X 8 yds. adjoining the Wells Hill Park Bowling green for the erection of a fieldhouse and lavatory accommodation."18 After reviewing previous negotiations, the Library Board agreed "to lease a small area of property adjacent to the Wychwood Library to the city to be used to erect a clubroom for the use of the Wells Hill Bowling Club," the Globe and Mail reported the following day. "The lease will be under a contract to be drawn up by the City Solicitor, and will stipulate that the property will be returned to the library board should they need it in the future for library purposes."19 Charging $1.00 per year, the Board also insisted that "that any building to be erected shall be constructed of brick." A brick clubhouse clad in white stucco opened on the library property in 1948.

On 9 May 1951, Library Board considered another request from the bowling club, determining this time:

That the request of the Wells Hill Bowling Club to be permitted to move their storehouse so that it will encroach on library property approximately 8 ft. x 3 ft. be granted on condition that the officers of the Club state in writing that they will remove this storehouse from library property at the Library Board's request should the Board ever need the land, and that it be understood that the Library Board cannot entertain any further request for encroachments.20

New clubhouse facilities are being incorporated into the renovation and enlargement of Wychwood Branch scheduled to start in 2017.

Notes

1 Toronto Public Library Board, Minutes, 17 April 1914, 100.

2 "Want site for library," Toronto Star, 30 April 1914, 4.

3 City of Toronto By-law 6444, passed 5 May 1913. City of Toronto By-law 6606, passed 21 July 1913.

4 Toronto Public Library Board, Libraries and Finance Committee, Minutes, 5 May 1914, 117.

5 "Library is inadequate," Toronto Evening Telegram, 16 February 1915.

6 "Hillcrest Library going to cost $17,000," Toronto Daily Star, 2 March 1915; "Wychwood to have 17,000 library," Toronto Evening Telegram, 3 March 1915.

7 James G. Forman, letter to George H. Locke, 1 May 1915, Toronto Public Library Archives, L2, Box 14a.

8 Ibid.

9 CLC, Bertram to Locke, 17 May 1915.

10 "Libraries Go Ahead," Toronto World, 30 June 1915, 3

11 Wychwood Public Library, Toronto World, 27 July 1915.

12 Toronto Public Library Board, Libraries and Finance Committee, Minutes, 7 November 1916, 198.

13 Alfred V. Hall, "Toronto Branch Libraries Ground Treatment," Construction, v. 10 (November 1917), 392.

14Rita McBride, "The Wychwood library," Toronto Mail and Empire, 22 January 1921.

15 Toronto Public Library annual report 1925, 29.

16 Wells Hill Lawn Bowling Club, Wells Hill Lawn Bowling Club : 1925 (Toronto, [The Club], 1954.

17 Toronto Public Library Board, Minutes, 14 November 1944.

18 Ibid., 13 March 1945.

19 "Lease clubhouse site," Toronto Globe and Mail, 14 March 1945, 8.

20 Toronto Public Library Board, Minutes, 9 May 1951.